When Vybz Kartel was released from a Jamaican prison in August, I opened Spotify and began nostalgically taking part in dancehall classics. My enjoyment was short-lived after I came across two violently homophobic songs by the reggae and dancehall artists Sizzla and Capleton. Didn’t we go away all this behind years ago? The songs had been recorded in 2005 and 1993; each artists subsequently signed the Reggae Compassionate Act and renounced homophobia. So why are these songs on Spotify in 2024 – significantly when different infamously anti-gay songs aren’t?

Buggering, by Capleton, is an abrasive condemnation of intercourse between two males that seemingly calls – in lyrics printed on Spotify – for public beheading and capturing as punishment. Sizzla’s Nah Apologize was a response to the Cease Homicide Music marketing campaign, which referred to as for dancehall artists to apologise for his or her anti-gay anthems and stop taking part in them. Sizzla’s lyrics aren’t simply unrepentant, however advocate the deadly stoning of “biblical days”.

Spotify’s hate content policy says: “We don’t tolerate hate content material that expressly or principally promotes, advocates, or incites hatred or violence towards a gaggle or particular person primarily based on traits, together with race, faith, gender identification, intercourse, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, veteran standing or incapacity.” But these songs slipped via the web. Was Spotify conscious they had been on the platform?

Returning to Spotify’s coverage web page, I seen a caveat: “Cultural requirements and sensitivities fluctuate broadly. There’ll all the time be content material that’s acceptable in some circumstances however is offensive in others.”

At floor stage this appeared honest: to censor rap, rock and any variety of genres in between for problematic content material could be the beginning of a slippery slope. Even some white supremacist acts managed to stay on the platform for a spell after others were removed. Is it problematic to censor Jamaican artists and never others?

A Spotify spokesperson confirmed that the corporate is conscious of the songs. “The tracks and artists in query have been reviewed, and the content material doesn’t violate platform insurance policies,” it stated in an announcement.

The songs had been checked by people, Spotify stated, not simply by AI scanning for set off phrases. It stated the tracks had been additionally accessible on Amazon, Apple and YouTube, offering a context of wider advocacy. In reaching their choice, Spotify’s human reviewers – which embody in-house and exterior consultants, and a panel of specialists on its Safety Advisory Council – had taken account of Capleton and Sizzla being Rastafarians.

This final level is fascinating however controversial. Some claim that Rastafarians’ views on homosexuality derive from interpretations of the Previous Testomony: Sizzla’s Spotify bio describes him as “a member of the militant Bobo Ashanti sect [who] typically courted controversy together with his strict adherence to their views, significantly his aggressive condemnations of homosexuals”.

Spotify doesn’t write all artist bios – some are written by artists or contributors – however I requested Spotify whether or not its reviewers had due to this fact deemed Sizzla’s lyrics an expression of cultural and spiritual beliefs. They didn’t reply.

Some artists have self-censored: Buju Banton stopped performing his famed 1992 homophobic homicide monitor Increase Bye Bye in 2007 and voluntarily eliminated it from streaming websites in 2019, sharing an announcement that he recognised that “the tune has prompted a lot ache to listeners, in addition to to my followers, my household and myself”. Different tracks reminiscent of Elephant Man’s 1999 monitor Nuh Like have both been eliminated or had been by no means on the platform to start with. “Some violative tracks have been eliminated up to now whereas others have been eliminated by the rights holders,” Spotify stated.

Glenroy Murray of J-Flag, Jamaica’s LGBTQ+ rights organisation, thinks educating audiences is the best way ahead, moderately than merely eradicating the tracks from streaming platforms. “If a society or tradition is fertile floor for hate music, censorship by itself solves nothing,” says Murray. “Spotify and different streaming providers have a troublesome activity in figuring out hate content material. A deeper understanding of dancehall reveals that [just like rap] it requires the efficiency of poisonous masculinity and can also be very sexist.”

He proposes that streaming platforms ought to add warnings and disclaimers, as Disney does relating to older, poorly dated content material. “The same method may be tried with music so youthful audiences can perceive the shifts in dancehall, rock and rap.”

In recent times, new generations of dancehall artists have embraced LGBTQ+ rights. Shenseea and Spice have embraced the queer group and showcased same-sex relationships of their visuals; each carried out at Toronto Satisfaction. In Jamaica, whereas gay sex remains illegal, there at the moment are Pride events on the island, and DJs at radio stations and stay occasions have tacitly agreed to not play homophobic songs.

On the identical time, says Murray, some LGBTQ+ audiences in Jamaica have reclaimed a few of this materials as “a type of visibility and resistance in dancehall areas, as in some ways they’re the one songs that reference the group. Elimination of them would act as a elimination of that historical past of resistance. We might lose the chance for dialogue that these songs create for queer individuals with their pals and households.”

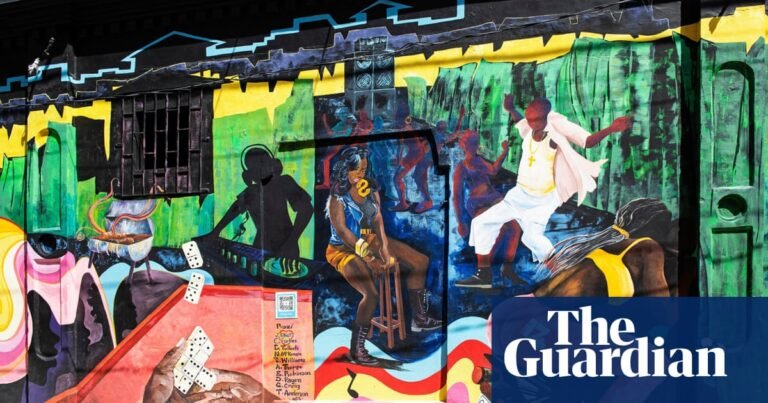

Dr Aleema Grey, curator of the British Library’s Beyond the Bassline exhibition of Black British music, factors to the existence of LGBTQ+ London membership evening Queer Bruk, geared toward queer POC, for instance of this reclamation: the way it “totally embraces dancehall and sees the juxtaposition of two males kissing in a membership listening to Buju Banton as a part of their custom of defiance and wonder”.

Grey says that homophobic lyrics are only a small a part of “dancehall music’s liberation theology of intercourse, gender identification and race because the inventive expression of a individuals” and that the music and tradition should not be misunderstood.

“For these with histories of violence, erasure, subjugation and absence, like within the Caribbean, music is a cartography of the previous and current, to know who we’re. Associating Rastafarianism with homophobia is an unhelpful narrative. The problem,” she says, “is the place you draw the road.”

And the way far you retrace this historical past: Trinidadian LGBTQ+ activist Jason Jones blames British colonial-era legal guidelines (such because the Buggery Act, in power from 1533 to 1828 in Britain and still in force in former British colonies together with Jamaica) and American televangelism for spreading homophobia all through the Caribbean.

“Individuals develop and study at their very own tempo,” he says. “We’d like extra nuance and empathy when addressing homophobic music within the Caribbean. A worldwide north method to human rights doesn’t all the time work for the worldwide south and might typically trigger extra hurt. I might moderately see assets and vitality put into uplifting younger queer dancehall and soca artists and getting their music out to the general public. Let’s reply homophobic music with proudly joyous queer music.”